The 70th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision that found racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional is Friday, May 17.

One of the court cases that ultimately led to that decision began in Virginia, with calls for newer and better school facilities for Black students. This VPM News series examines the issue of school conditions — then and now — to unpack why so many Virginia schools are in disrepair, especially in districts like Richmond Public Schools, which remains largely segregated.

The series’ third and final installment explores possible solutions to Virginia schools’ infrastructure issues, first looking to Washington, D.C., where the city replaced 70% of its schools in 25 years.

Nature inspired the design of John Lewis Elementary School in Northwest D.C.

"We have our outside treehouse. I was pretty scared when I first saw that,” said Principal Nikeysha Jackson. “The kids loved it. It is their favorite thing in the building."

The district’s first net-zero building has all the bells and whistles: an outside amphitheater, eco-friendly ponds and solar panels. And as Jackson points out, all of the classrooms have retractable garage doors.

“Usually in the mornings, they'll be open as kids are walking in, and then they close them,” Jackson said. Some people teach with them open all day long.”

This new building is part of a long-term city effort to get all its schools in good shape. Not all of them are as impressive as John Lewis, but many were in worse shape a few decades ago.

‘Planning isn’t reacting’

In 1992, a group of parents filed a lawsuit against Washington over fire code violations. Mary Filardo, executive director of the 21st Century School Fund, had children in D.C. Public Schools at the time.

She said there were a number of fire code violations: “because doors were chained shut, so that kids wouldn't be able to get out. Because the doors weren't working properly. There were breaches in the plaster and in the ceilings, because of roof leaks and other problems.”

Filardo said the lawsuit did lead to some fixes, but more often than not, the fixes were bandages. She said the district’s efforts to address problems seemed too small in scope — like a campaign to ensure there was enough toilet paper in city schools.

“I'm like, ‘What the hell, you know, toilet paper in the bathrooms and the toilets don't flush,’” Filardo said. “They had no stalls around them, because they were busted.”

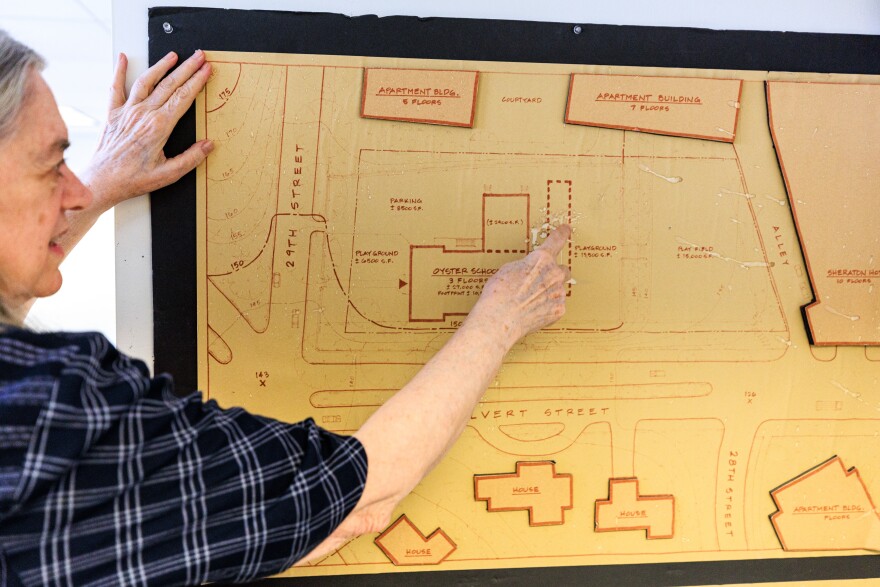

She said conditions at D.C. schools were so bad, the district threatened to close some of them. That's when Filardo and other parents decided to help DCPS put together a long-term master plan for new school construction.

Filardo said they went to the superintendent and asked: “‘Do you know how to do a master plan?’ And he said, ‘No,’” Filardo said. “And I said, ‘Well, we'll help you.’ Now, we didn't know how to do a master plan back in 1993, either. But we knew how to find people who did.”

With a group of experts — along with legislation, guidelines and funding details from D.C. City Council — Filardo said a long-term plan was developed, which was key to the transformation of schools.

“You have to plan for something different,” Filardo said. “If you just say, ‘Oh, well, this is always what's going on,’ then essentially, you're just contributing to a spiral to nowhere. And so, planning isn't reacting, which is very often what you see in school districts.”

Filardo admitted the plan wasn’t perfect. Others, like Erika Roberson, agree.

Roberson, a policy analyst with the DC Fiscal Policy Institute, explained the weighted formula the city now uses when deciding which schools to upgrade first: facility conditions, demand, community need and the number of at-risk students attending any particular school.

Roberson is concerned about what’s interpreted as “demand,” which is weighted at 20% in the formula; it’s the second most consequential category behind facility conditions, which accounts for 55%.

“Schools that have larger enrollment declines — so the schools in Wards 7 and 8, typically — aren't going to have large demands, because they don't have the same high-level programming as some of the schools in the more resourced areas,” Roberson said.

Disparities across district lines

Richmond Public Schools has acknowledged it’s been playing Whac-A-Mole with infrastructure issues. The district created a facilities plan in 2017, but some schools — like Woodville Elementary — were and still are on the list for needed upgrades. RPS is just now developing a plan to build a new Woodville.

Meanwhile, Chesterfield County’s long-term school facilities plan is carefully charted to build and renovate numerous school buildings over the next five years.

Josh Davis, chief operating officer for Chesterfield County Public Schools, told VPM News the division has opened nine new elementary schools in the past five years. Meanwhile, Richmond Public Schools has struggled with getting a handful of new schools built in the same timeframe.

RPS also has about one-third of the student population of CCPS, but nearly two-thirds the number of total elementary, middle and high schools to maintain (not including specialty or technical schools in either district). Chesterfield’s facilities department also has more staff and resources than Richmond’s — an example of disparities across district lines.

Some experts have raised another possible solution to the imbalance: consolidating school districts. It’s not a new idea, either: In 1970, a U.S. district judge wrote that full desegregation of Richmond’s schools would require a single regional system, combining Richmond with Henrico and Chesterfield county schools.

“We know that school district boundary lines have come to structure the majority of segregation, so that kids are now sorted more between districts and to racially-separate districts rather than within districts into racially separate schools,” said Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, a VCU professor who researches school desegregation.

She said the scale of consolidation that would be necessary today to make an impact is different from even a decade ago, and would likely require adding more surrounding localities to the effort beyond just Chesterfield and Henrico.

But Siegel-Hawley said school districts don’t necessarily need to consolidate to collaborate in a meaningful way. For example, she said, they could start with some level of resource sharing or joint planning for something like school construction.

“You can think about the school district boundaries as being elastic. Like, you could stretch them out further and create a bigger district or you could think about them being more porous, so that it’s easier for kids and resources to flow across them,” Siegel-Hawley said. “It feels too much like a zero-sum game in our current setup of fragmented, local governments.”

For example, Siegel-Hawley said, it’s an “inefficient use of resources” if Chesterfield or Henrico was to build a new school close to the city boundary if Richmond was considering closing a school nearby.

A few years ago, a Virginia legislative commission estimated it’d cost about $25 billion to replace or rebuild all of the failing K-12 buildings across the state.

But Virginia localities have been mostly on their own to pay for new schools for nearly a century. During the Great Depression, the federal government funded close to half of the cost for new school construction. Now, Virginia localities finance nearly 90% of that cost.

As part of the Byrd Road Act — named after former Gov. Harry Byrd, who vehemently opposed school desegregation — a deal was struck in the 1930s in which the commonwealth would pay for road maintenance as long as localities handled school construction.

“[Localities] primarily rely on property taxes and debt,” U.S. Rep. Jennifer McClellan told VPM News in 2022, when she was a state senator. “For many localities, especially our fiscally-stressed localities, they're at debt capacity, and they just can't raise enough money through property taxes to pay for all of their needs, and school maintenance and construction.”

That year, McClellan introduced multiple pieces of legislation aimed at lessening the financial burden on localities for construction.

“We've got to step up as a state and make sure that every child in Virginia is learning in a building that shows we care about them,” McClellan said.

But state grant funding for school construction in the recently passed state budget is less than one-fifth of what it was during the previous biennium: $160 million compared to $850 million. Now, the grants’ primary funding source is a portion of the state’s casino revenues; the $850 million was largely funded by a one-time surplus.

There are also state-backed loans available to school divisions, but localities still have to pay down the principal and interest.

Eight states pick up the tab for at least 50% of school construction costs, while several other states pay for at least 25%. Virginia pays 10%, compared to the national average of 22%.

The 21st Century School Fund and the National Council on School Facilities have put forth a set of “good stewardship standards” based on best practices in the building industry. They call on school divisions to spend 3% of the current replacement value of their school buildings annually on maintenance and operations — routine and preventative repairs — and 4% on capital investment. The latter includes periodic replacement of key components, like windows and doors, as well as working through backlogs of deferred maintenance.

In a 2021 report, the organizations found that in the fiscal years from 2009 through 2019, Virginia spent an average of nearly $2 billion less than the proposed standard for capital investment — the ninth-largest gap in the nation — and an additional $527 million below the recommended level on maintenance and operations.

Until last year, school facilities weren’t part of the state’s standards of quality — which are intended to prescribe the needs of Virginia’s public schools, as well as the funding to cover those necessities. While legislation passed in 2023 added facilities to the standards of quality, they haven’t been fully funded.

Jeff Bourne, a former state delegate and Richmond school board member, told VPM News in 2022 that he thought the Virginia Constitution should be revised.

“It says endeavor [to provide a quality education],” Bourne said. “I just want to take that ‘endeavor’ out and just put ‘shall,’ because that's pretty clear. And then we have to put our investment in these standards of quality, which are the bare minimum standards. And so, if we're really going to hang our hats on creating a world-class education for everyone, then we know it's going to cost, and we've got to pay for it.”

Earlier this year, Gov. Glenn Youngkin vetoed legislation that would’ve allowed localities to raise funds through voter referendums for a 1% sales tax increase to build new schools. Right now, only a handful of Virginia jurisdictions have that authority. It’s been an attractive option, particularly in rural localities where school districts have unique needs. In those areas, raising property taxes often isn't seen as a viable option to help build new schools.

Filardo, the D.C. schools expert, said that “by far, the rural districts have had the least capital investment,” and that “poor minority communities have had far less capital investment than more affluent communities.”

But it takes more than a good plan and funding to truly address the problem.

Filardo said the community and policymakers need to be determined to change the status quo.

“You sit down at the table, and you let the elephant in the room,” Filardo said.

Until the elephant is acknowledged by all parties — individual school districts, and their localities, states and the federal government — she said “to some extent, somebody's got to be ringing those bells and saying, ‘Ah, not OK.'”

Part 1 looks at the current state of Richmond Public Schools and the consequences of its aging facilities.

Part 2 looks at the history of Prince Edward County Public Schools, where the fight for equal schools in Virginia began.