‘All these people are heroes’

Meet the men behind the projections on the Lee monument

Brian Palmer | 8/13/2020, 6 p.m.

Dustin Klein and his partner in projection, Alex Criqui, have lost count of the number of days they have been making their art at the Lee statue on Monument Avenue at the area protesters call Marcus-David Peters Circle.

“We came out one night and said, ‘We’re going to project on the monument and see what happens,’ ” Mr. Klein said, as he and Mr. Criqui monitored images of prominent and less recognizable African-Americans they were projecting onto the Confederate monument from a tent just outside the circle.

“We did not expect to come out here 40 days in a row afterward,” he said. But there they were on a humid and stormy July night, when rain threatened to drive them away, but didn’t.

Mr. Klein and Mr. Criqui, both 33-year-old white men, grew up in Chesterfield and have lived in Richmond on and off for the past decade. Like so many other people, the brutal killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer propelled them into the streets.

They wanted to do something to respond to the tragedy without “overpowering anyone,” Mr. Criqui said. But they recognized that as white men, they needed “to be conscious of our role here given the racial component,” he continued.

“I think both of us knew this isn’t a movement where we can get up and give a speech. It’s not our place to do that,” Mr. Criqui said.

But what they could do, he said, is amplify the messages from the Black Lives Matter movement — by making what are essentially “bigger signs.”

At the same time, they would be giving the public “a different contextualization” for “a symbol of white supremacy,” Mr. Klein said.

In doing so, they added, they’re helping Black Lives Matter claim the space around the Lee monument.

Thousands of people have been drawn to the site since late May, many taking photos of the six-story statue with the duo’s projections of Black people superimposed over it.

Mr. Klein and Mr. Criqui recognized that as a pair, they had a particular set of skills they could apply to their project. Mr. Klein had the technical expertise to create the presentation — he does this work for a living — and Mr. Criqui could bring his understanding of history, his major at Virginia Commonwealth University, to bear. They worked together on the design.

“I think in some ways this felt like a way we could use our voices in an appropriate way,” Mr. Criqui said, his eyes still on the image of Harriet Tubman superimposed that night on the statue’s pedestal.

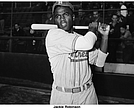

They grabbed their first visual material, a video comprising portraits of 46 African-Americans killed by police, from the national Black Lives Matter Facebook page. Since then, they have added many other figures — all African-American — to their nightly repertoire.

On this July night, they featured the late Congressman John Lewis of Georgia, a lifelong fighter for civil rights. They featured projections of him both as the elder statesmen before his death last month and as the young activist standing proud on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965.

Their illuminations also have included Frederick Douglass, Maggie L. Walker, journalist and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells and soldiers of the United States Colored Troops, who fought during the Civil War to free the nation from slavery.

“When we put up Harriet Tubman, when we put up the Union soldiers, there’s a strength and resolve in their actions and in their history and on their faces that I think is also a source of resilience for our community out here,” Mr. Criqui said.

The men also have been open to suggestions from visitors to the circle. A professor from Tampa, Fla., who had driven up to Richmond asked them to include Black people who led uprisings of the enslaved, such as Nat Turner and Richmond’s own Gabriel. Their likenesses are now in the rotation.

For all their pride in their work, Mr. Klein and Mr. Criqui are keenly aware that the issue of race is never too far from the surface.

“We’ve been getting a lot of praise through all this, which has been humbling. But it’s also slightly problematic,” Mr. Criqui said. “I try and tell people that we’re just the icing on the cake.”

Mr. Klein and Mr. Criqui are clear about what the “cake” is. They pointed toward the image in the monument, not a person’s likeness, but massive words: “No America Without Black America.”

“That’s really what we were trying to express here,” Mr. Criqui said. “There’s a beautiful history and there are so many heroes to be proud of. And so many of these people are actually the best Americans you can think of. I cannot think of a better person than Martin Luther King Jr. or Harriet Tubman,” he said.

“George Washington is nowhere as noble as those human beings,” Mr. Criqui continued. That’s because George Washington never really had to suffer, he said.

“He never really had to work against the odds. He was always the child of privilege. He was always the dominant race. He owned other people. He’s not a hero,” Mr. Criqui said. “John Lewis is a hero. All these people are heroes.”