Defunct

Richmond Slave Trail Commission, formed in 1998 by City Council to advocate for educating people about the enslaved and the city’s long and sordid history with slavery, no longer exists

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 10/14/2021, 6 p.m.

The Richmond Slave Trail Commission – an advocacy group created by Richmond City Council to raise awareness of the role slavery played in the capital city’s history – is defunct.

Little apparent notice has gone to the governing body that created it and appoints the membership.

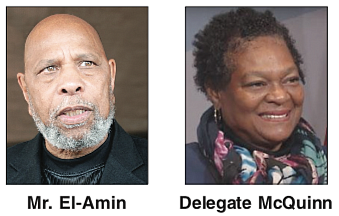

“That’s horrible, horrible,” said former City Councilman Sa’ad El-Amin, who led the effort to create the commission in 1998 and served as its chair until he was forced to resign his council seat in 2003 amid legal woes.

Delegate Delores L. McQuinn, who has chaired the commission since then, confirmed that the group has not met in at least two years and has no intention of meeting any time soon.

The commission is best known for creation of the Slave Trail that winds through South Side and Downtown; excavating the site of the notorious Lumpkin’s Jail slave trading post in Shockoe Bottom; and placement of the Slavery Reconciliation Statue on East Main Street near 14th Street.

Although there is no public record of City Council being given notice or approving the decision, Delegate McQuinn said she assented to Mayor Levar M. Stoney’s request to have the commission folded into the Shockoe Alliance.

The mayor created the alliance two years ago to plan for the future of Shockoe Bottom, the city’s birthplace and later one of the largest centers of the slave trade before the Civil War. It has been listed on the national register of historic places since 1983.

The proposal that the alliance released in late summer would make that slavery history a centerpiece of the area’s future, including creation of a memorial park and museum-style pavilion at Lumpkin’s Jail, a place of horrors dubbed “the Devil’s Half- Acre” that ironically became the birthplace of Virginia Union University after the Civil War.

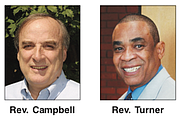

The commission still exists on paper, according to records in the City Clerk’s Office, but was down to just two additional members when it essentially folded — the Rev. Benjamin P. Campbell, chair of GRTC’s board, and the Rev. Sylvester L. “Tee” Turner, pastor of Pilgrim Baptist Church.

In a meeting with the Free Press, Delegate McQuinn, Rev. Campbell and Rev. Turner said their vision is to have City Council convert the commission into a foundation that would raise $100 million to $150 million to create a national slavery museum that would include the Lumpkin’s Jail site.

Richmond commissioned the Smith Group, a nationally recognized museum consulting organization, to conduct a feasibility study. The results are posted on the city’s website along with other information about the Shockoe plan at www.rva.gov under the “Planning Development Review” section.

The fact that there are only three members remaining on the Slave Trail Commission reflects the blockade that Delegate McQuinn imposed on new appointments with the support of Council President Cynthia I. Newbille, 7th District, who is listed as a member.

Dr. Newbille, who succeeded Delegate McQuinn on the council after she was elected to the General Assembly, did not respond to a request for comment.

However, the lack of new appointments was first noticed in 2009 and became more public in 2012 when Mr. El-Amin and the Richmond Branch NAACP began raising the issue of dwindling numbers. While the issue has been raised by others since, no further appointments have been made.

To Mr. El-Amin, the commission’s decision to shut down represents a betrayal of its mission to be an advocate for Black history. He said he designed the commission to be a counterweight and advocate for educating people about the enslaved at a time when Confederate monuments dominated the city’s landscape. Nine years ago, as he battled in court to halt Virginia Commonwealth University from continuing to park cars on Richmond’s first cemetery for enslaved and free Black people at 15th and Broad streets, Mr. El-Amin expressed concern that the commission was not leading the fight.

With the help of then Gov. Bob McDonnell and the state legislature, VCU gave up the site of the African Burial Ground, which is now in the commission’s hands.

But since the asphalt was removed, Mr. El-Amin noted Wednesday, the commission “has left (the site) as a cow pasture” rather than turning it into a proper memorial site for the enslaved.

He called the museum proposal a “pipe dream” and expressed hope that City Council would re-energize the commission by appointing new people “to carry out its original mission, which is to tell the story of our enslaved ancestors.”